Ontario Nature Blog

Receive email alerts about breaking conservation

and environmental news.

© Lora Denis

March 13, 2024–Kellsie Bonnyman

Singing Sands Beach, Bruce Peninsula Provincial Park © teachandlearn CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Over 12,000 hectares of protected areas in southern Ontario – about the size of Bruce Peninsula National Park – have been officially accepted into the Canadian Protected and Conserved Areas Database (CPCAD). Spearheaded by three municipalities and one conservation authority, the inclusion of these lands marks an important step towards achieving Canada’s commitment to protect and conserve at least 30 percent of lands and waters by 2030, otherwise known as the 30×30 target.

The 30×30 target is just one of the twenty-three targets that make up the Global Biodiversity Framework, which was ratified by nearly 200 countries – including Canada – at the 2022 Conference of the Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. The 30×30 target emphasizes the need for ecological representation, connectivity and equitable governance of protected areas which recognizes and respects the inherent rights of Indigenous Peoples and communities. It represents a key pathway to halting and reversing the dual crises of climate change and biodiversity loss.

To ensure that sites are eligible for inclusion in CPCAD, they must be assessed to ensure they meet the pan-Canadian standard for protected areas.

The criteria include:

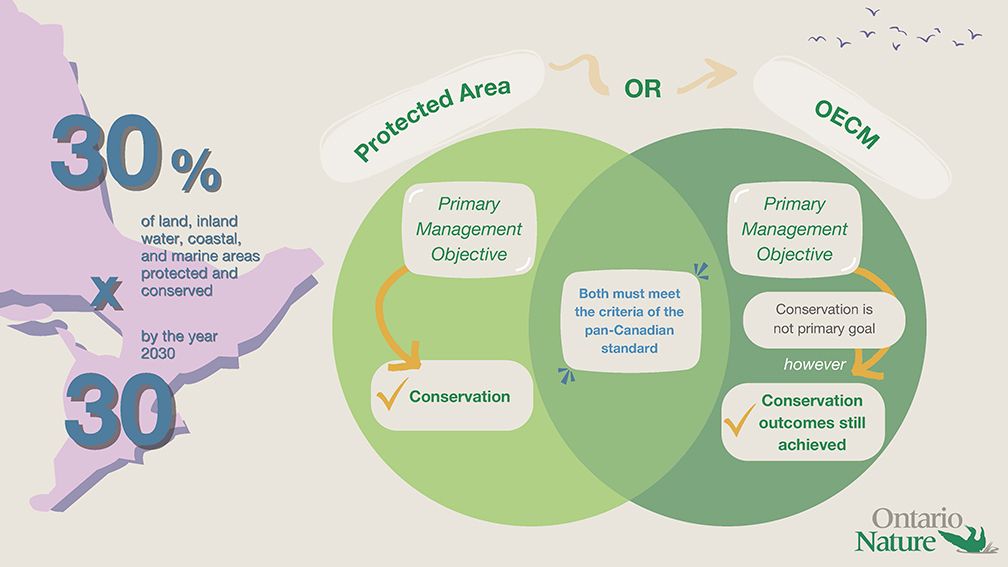

Once it is determined that sites meet the standard, they are classified as either 1) protected areas or 2) Other Effective area-based Conservation Measures (OECM). The difference between the two can be seen in Figure 1.

Local governments and conservation organizations in southern Ontario play a critical role in protecting natural areas, which are often close to or even nestled within dense urban centers. They juggle multiple competing objectives while planning for growth and balancing the increasing need to safeguard the natural environment for future generations.

The following municipalities and conservation authority deserve to be celebrated for implementing strong management policies and on-the-ground conservation efforts to protect biodiversity in their regions:

These near-urban protected areas are vital habitats, corridors, and rest-stops for wildlife, including species at risk. They also help mitigate flood risks, reduce heat island effects in urban areas and enhance climate resilience while providing important access to nature.

Ontario still has a long way to go to achieve 30×30, as less than 11 percent of our lands and waters are recognized as protected. To meet this target, it will take all hands-on deck. Subnational governments, land trusts, conservation authorities, and community stewardship groups have an important role to play in meeting the target. This includes having sites assessed to determine whether they already meet the criteria.

Ontario Nature will continue to partner with local leaders to conduct assessments of protected and conserved areas.

To support local and municipal biodiversity conservation at broader scales, Ontario Nature is part of the Municipal Protected Areas Project, a national initiative funded in part by the Government of Canada. Partners include Nature Canada, the Alliance of Canadian Land Trusts, BC Nature, and Wildlands League. The coalition works across southern Canada to support the protection of near urban nature by sharing wise practices and policies, encouraging local partnerships and addressing barriers to conservation.

Gananoque Lake Nature Reserve © Smera Sukumar

You refer to conservation outcomes. Exactly what does that mean?

We must convince individuals to put much needed pressure on THEIR COMMUNITY MUNICIPAL GOVERNNENT to be environnental conservationists. It is critical to sustaining vibrant, healthy communities. COMMUNITIES THAT WILL BE IN A HEALTHIER, SAFER POSITION TO FIGHT IMPACT OF INEVITABLE CLIMATE CHANGET THAT WE ARE LIVING IN NOW.

THE POLITICIANS OF THE 21ST CENTURY MUST SUPPORT, ADVOCATE ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION IT IS OUR CHILDREN, GRANDCHILDREN’S FUTURE. What could be more important.

Thank you for your detailed reply, Kellsie. I was just trying to create a dialogue about this topic with my original post. One might call it a “conservation conversation.” Also, I hold the particular view that I shared in my first post because when it comes to the goal of protecting the natural areas of our country, I do not wish to see the federal and provincial governments let off the hook as the result of a possible overdependence on locally or regionally generated OECMs. The feds and the provinces have the power (in cooperation with First Nations) to protect vast amounts of ecologically important lands and waters in Canada, something that is beyond the capability of municipalities and other local bodies through the use of mechanisms like OECMs. Having said that, I do recognize the undeniable value of local conservation actions and local buy-in to the successful preservation of our natural heritage. In the end, it all adds up and will hopefully get those of us who care about nature to where we want to go.

Hi John — Kellsie responded above. Thanks for your thoughtful comment.

Hi John. Thank you for expressing your concerns. We appreciate and share your desire to hold a high bar for conservation in Ontario.

We’d first like to clarify the national approach to OECMs. Canada follows international OECM guidelines and standards established by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. While it is true that OECMs are sites which typically exist for purposes other than conservation, fortunately, these areas must be held to the same national standard as protected areas. This means OECMs must be managed in ways which prevent and restrict activities harmful to biodiversity. They must also yield positive, long-term biodiversity conservation outcomes, even though their primary objective is not conservation. For example, one of the first OECMs recognized in Canada was in Northumberland County Forest, which Ontario Nature is proud to have supported. The forests’ Special Management Zones support year-round protections against development while delivering long-term conservation outcomes.

Like protected areas, OECMs represent a high bar for conservation. However, we recognize that collectively we must guard against the risk that this bar could be lowered, as we’ve highlighted in previous blogs (https://ontarionature.org/meeting-30-x-30-an-ambitious-target-blog/).

Note: To see the percentage of OECMs and protected areas recognized across the country, please find the attached link to the national database (see summary table – https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/national-wildlife-areas/protected-conserved-areas-database.html).

Great article, and I’m glad to learn about this progress towards 30 x 30, with local governments stepping up to do their part.

Of the lands and waters already deemed to be protected in Ontario and Canada, what percentage is represented by OECMs? Is there a national standard or guideline for such a percentage? I ask these questions in part because if the primary management objective of OECMs isn’t conservation, then I believe that they should not be included in the 30 X 30 protection target. Instead, they should be considered a benefit above and beyond that

target. Personally, I would rather see the 30 X 30 goal strictly reserved for lands and waters for which conservation is the main priority and whose protection will be treated as firm and sacrosanct, and not for areas that can have the effect of contributing to biodiversity conservation but that may also be “potentially” subject to future negative alterations by municipalities or other local or regional entities.