Ontario Nature Blog

Receive email alerts about breaking conservation

and environmental news.

© Lora Denis

Nabish Lake © Kristen Setala

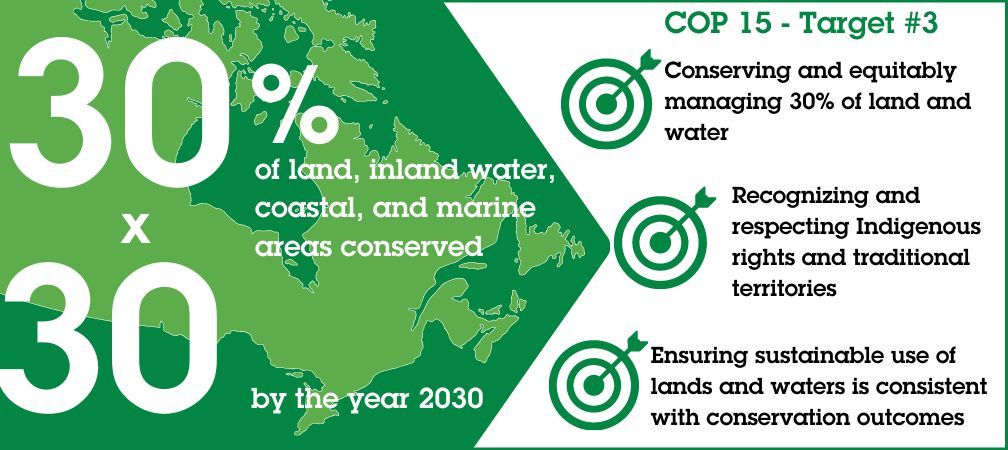

The phrase “30 x 30” dominated the headlines from COP15 in Montreal last December. It’s the international commitment to protect at least 30 percent of the world’s lands and waters by 2030. Formally known as Target 3, it is just one of 23 targets intended to halt and reverse biodiversity loss.

It’s an ambitious target, and one that Ontario must contribute to if Canada is going to meet it. There are many ways to get there. Increasing our provincial protected area system is a conventional and necessary approach. Recognizing Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas and other lands stewarded under Indigenous governance will also be critical to success. Another important element will be adding to the conservation lands held by land trusts, municipalities and conservation authorities.

Beyond this, there is an opportunity to recognize and strengthen protection through “other effective conservation measures,” often referred to as OECMs. OECMs are areas that are managed in ways that effectively conserves biodiversity over the long term, even if that’s not the reason they exist. One of the earliest OECMs reported for Canada was in Northumberland County Forest – an achievement Ontario Nature was proud to support.

There is broad agreement that OECMs can complement more conventional protected areas networks and contribute to Target 3. Recognizing OECMs acknowledges effective long-term conservation that is taking place outside currently designated protected areas under a diverse set of governance and management regimes.

The OECM classification is a new one that must be used carefully. Ontario has worked with the Government of Canada and other provincial and territorial governments to agree upon specific criteria that must be met for OECMs. To count as OECMs, areas must be managed in a way that leads to long-term, year-round biodiversity outcomes within a defined area. Those responsible for managing the area must be able to control all activities that are likely to impact biodiversity within the OECM boundaries. It’s a high bar to meet.

However, in the race to add up hectares to meet the quantitative target of 30 per cent, there is real risk that the bar may be lowered, and that the actual effectiveness of biodiversity conservation may be overlooked. Recent reports indicate that the pressure to meet the 30 per cent target may be causing Canadian decision-makers to consider counting areas as OECMs that don’t meet our own or international standards for effective, long-term biodiversity conservation.

Although Ontario has not committed to Target 3 or previous area-based biodiversity targets, the province has been careful in applying these standards to recognize land management practices that effectively conserve biodiversity on the ground. We urge the Government of Ontario to continue to hold the bar high. Ontario Nature is actively seeking out opportunities to enhance protections in areas under diverse types of land uses so that they can contribute to the 30 x 30 target. We are unequivocal in our position that Ontario should continue to count only what really “counts” for halting and reversing biodiversity loss.

Gananoque Lake Nature Reserve © Smera Sukumar

Thank you, John for your comments and for sharing the important information about the evidence in the scientific literature supporting the need for even more meaningful area-based protection.

A study published in the journal Science last year concluded that we need to conserve 44% of the planet’s land surface if biodiversity loss is to be halted. Personally, I think we should be aiming for an even higher protection target than that. (I believe that I heard or read somewhere in the past year that some scientists think the ideal goal should be 70%.) And yet here we are in Canada struggling to get to 30%. (Have we even reached 20% yet?) I know, I know, it all takes time. But that’s of no comfort to any species on the brink of extinction or to any Indigenous peoples at risk of losing their way of life because the natural world is being destroyed around them.

Thank you, Corina, for the last three paragraphs of your article. I agree that potential OECM lands and waters must be examined closely to ensure that they are not inappropriately used by governments or industry to pad their conservation figures and also to ensure that if they are approved for inclusion, they are managed in such a way that biodiversity is indeed preserved for the long term.