Ontario Nature Blog

Receive email alerts about breaking conservation

and environmental news.

© Lora Denis

Algonquin Provincial Park © Bill McDonald

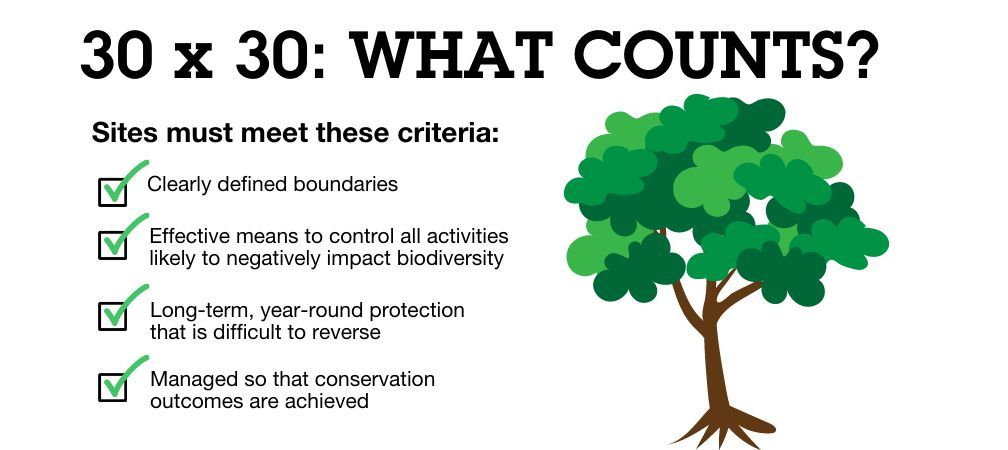

The conversation around protected areas is evolving in response to the challenge of protecting 30% of Canada’s lands and waters by 2030. What protected areas traditionally have been, and what they can be, encompass many forms. At Ontario Nature, we’re learning from the successes – and mistakes – of the past in our current work, and excited about the possibilities of the future.

In Ontario, protected areas started out simply as national and provincial parks. As families could afford to take camping vacations, more parks were established, with campgrounds, beaches and other family-friendly amenities. Then, as environmental consciousness grew through the 1970s and 1980s, planning for protected areas shifted to protecting ecologically valuable areas.

Large scale land use planning exercises established thousands of hectares of new protected areas to make land use decisions that resolved conflicts between resource extraction industries and environmental interests. However, the way protected areas were set aside didn’t respect Indigenous Peoples. To create people-free “wilderness” areas the Indigenous Peoples who cared for these lands since time immemorial were displaced and barred from using them.

Over time, the process of creating land use planning for protected areas got better at considering Indigenous rights and interests. The 2006 Keeping the Land strategy for the Whitefeather Forest involved a collaborative approach to deciding which areas should be protected, and how. Likewise, the negotiations with the Algonquins of Ontario have led to more collaborative decision-making for new protected areas.

In Ontario, protected areas that meet international standards are now being established and managed by governments, environmental groups, Indigenous communities and other environmental leaders through a range of approaches.

Non-governmental groups, such as land trusts, are creating their own unique protected areas. Ontario Nature’s own system of nature reserves count in the tally towards the 30 by 30 target. Municipalities are also playing an important role in protecting urban nature.

Since the 1990s, multiple protected areas have been established and are co-managed through collaborations between government and local Indigenous communities. One example is Thaidene Nëné National Park Reserve in the Northwest Territories which is jointly managed by provincial and federal government, and Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation.

In Ontario, Point Grondine Park is a backcountry wilderness park, solely owned and governed by the Wiikwemkoong First Nation. Many Nations are also self-declaring Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas on their traditional territories in accordance with Indigenous law, including Asubpeeschoseewagong First Nation in northern Ontario. The level of formal recognition of and respect for these areas by governments varies.

Our current work with FSC certified forests shows that forest industry leaders can play a valuable role in identifying potential protected areas using the best of western science while respecting the rights and interests of Indigenous communities.

In February, the federal government and nine First Nations announced that they are moving forward with negotiations for a marine conservation area spanning roughly 86,000 square kilometres across southern Hudson Bay and western James Bay. The next steps will be focused on extending protection 20 kilometres inland to include the carbon-rich peatlands that are under provincial jurisdiction.

We hope that these examples tell a story of possibilities for the future of protected areas in Ontario. There’s an opportunity for the province to support a new vision of protected areas. Is it up for the challenge?

Authors

Corina Brdar is the Conservation Policy and Planning Manager at Ontario Nature

Brittney Vezina is the Protected Places Project Coordinator at Ontario Nature

Gananoque Lake Nature Reserve © Smera Sukumar

Has the present Ontario government even formally endorsed the concept of protecting 30% of our province’s lands and waters by 2030? If not, that’s embarrassing.

I read in another recent Ontario Nature blog that less than 11% of Ontario is currently under some form of natural areas protection. And yet 87% of the province’s land mass is “Crown land” controlled and managed by the Ontario government. Well, here’s a solution: Just subtract 25% of that Crown land — the most ecologically important parts of it — and make it protected. Boom, done, we’ve then reached the 30 by 30 conservation target. (Obviously, it would be a little more complicated than that, as there would have to be consultations with First Nations in selecting and setting aside these lands for protection. But still, why is the Government of Ontario being such a laggard in all of this? There is clearly no sense of urgency on its part.)

(Note: The blog that I was referencing above is titled “Ontario’s 2024 budget is a chance to get in on federal funding for nature protection.” It appeared on Ontario Nature’s website on January 29, 2024.)

Thank you for your comment John. There has not been a formal commitment from the province to an area-based target – like 17% by 2020 or 30% by 2030 – for many years. As you note, with the portion of the province that is referred to as Crown land, the rights of Indigenous Peoples are essential to respect. There are also stakeholder interests in that part of the province. That’s why some of our work referenced in this blog is with FSC certified forests. There are opportunities there we hope will meet the needs of Indigenous communities, the forestry industry and other stakeholders, and be palatable to the government of Ontario.