Ontario Nature Blog

Receive email alerts about breaking conservation

and environmental news.

© Lora Denis

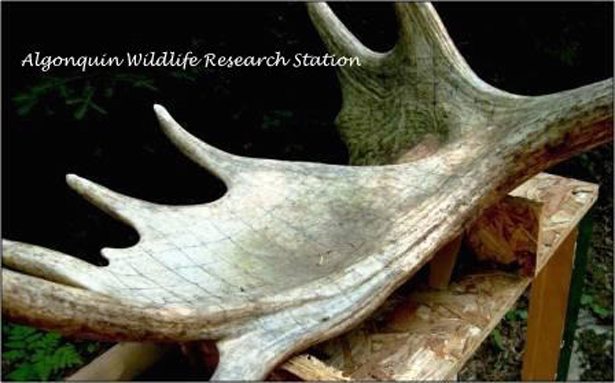

Aside from just being impressive ornaments, other wildlife could sure make use of moose antlers. The minerals in antlers, such as calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and sodium, are important for small mammals and other wildlife. Dropped antlers of deer, caribou and elk have equally important roles in nutrient cycling between different levels of food webs.

These reasons may seem very straight forward to most of us, but here is another reason to leave antlers be, which few of us might have ever considered. Moose antlers provide excellent homes for a tiny little species of fly, called the antler fly (Protopiophila litigata).

Antler flies have only just recently been added to the list of species in Canada. Discovering a new species is an exciting prospect that instantly raises a flurry of questions. Such was the case in 1994 when then student Russell Bonduriansky took notice of these curious insects with an inordinate fondness for moose antlers while conducting research at the Wildlife Research Station (WRS) in Algonquin Provincial Park. These flies had never been described before and therefore nothing was known about them.

One of the main questions arising from these flies is why we haven’t stumbled upon them until very recently? One hypothesis could be that they are extremely rare. But perhaps a more realistic hypothesis is that they live their entire lives on antlers, such that we only get a chance to catch them when we stumble across a set of antlers by accident. To test this hypothesis Russell marked flies with unique paint marking of numbers, letters, and colours to quantify whether each fly remained on a given antler for its entire life cycle.

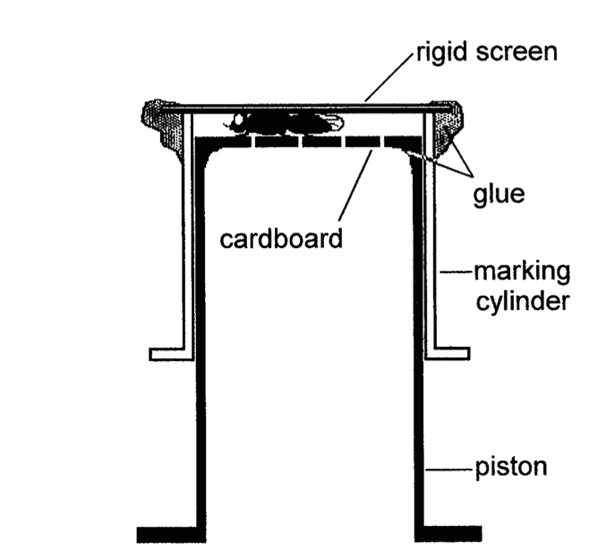

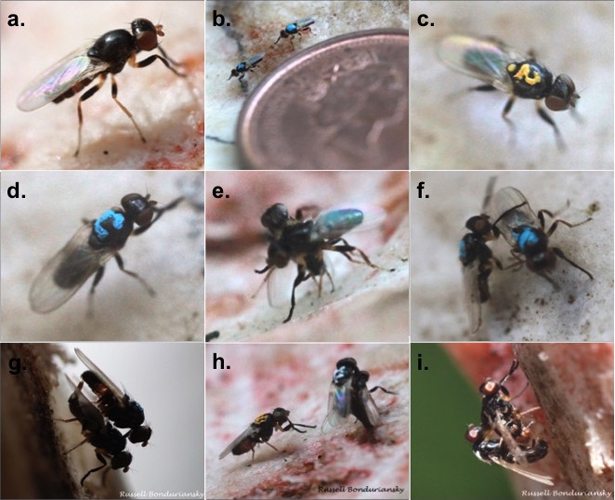

So, how did Russell design an experiment to answer this question? He brought several antlers back to the research station. The antlers were placed on wooden stands in the forest to facilitate close-up observations (Figure 1). He found a unique method to individually mark each fly found on the antlers (Figure 2, from Bonduriansky and Brooks 1997). At only 2-3 mm in length (half the length of a grain of rice!) marking these flies each with a combination of letters and numbers, was no simple task. The flies were gently immobilized by pinning a fly in a compression cylinder and marked using a very fine tip applicator (Figure 3). With flies uniquely marked Dr. Bonduriansky could follow each fly and record its activities and do so throughout the duration of its life.

So, do antler flies live their entire lives on shed moose antlers? Largely, yes. In general, eggs are laid in late summer and overwinter in the hollow bone matrix of the antler. Following hatching in the spring, larvae continue their development within the protective bone matrix. Late stage larvae are stimulated to migrate to the antler’s surface during rainfall and make heroic, if not also comical, “leaps” off the antler and into the adjacent soil. The larvae pupate in the soil and leaf litter in late May or early June, emerging as adults in approximately 12 days to re-occupy their natal antler.

Adults have a relatively short life span with a maximum longevity of approximately 30 days. Given this short adult lifespan, antler flies must pack a lot of activity into a short time frame. Male antler flies aggregate at breeding and egg-laying sites to wrestle other males, including those in mating pairs. The aggressive behaviour of male antler flies is extremely combative and some battles can last up to 30 minutes! Males are virtually miniature gladiators defending their own territories (e.g. resources such as food and egg-laying sites), combating for access to females, mate guarding against rival males, and even fending off other insects that step onto the antlers. The Latin name of antler flies is Protopiophila litigata where litigata rightly refers to the aggressive behaviour that Russell saw during his observations, from liti (Latin litis) meaning “dispute”, and gata (Latin ago) meaning “to carry on”. The battles can be quite costly as well and sometimes involve the loss of a leg or damage to the wings.

Females have a larger body size (1.9-3.1 mm) than males (1.6-2.8 mm), likely an adaptation to support greater fecundity (reproductive capacity, i.e. larger body size equates to more eggs). The females reject males smaller than themselves, selecting instead for large body size, robustness, and fighting prowess, but surprisingly, males are the choosier sex, preferring females based on their “fatness” (relative abdomen width), which is indicative of the amount of mature eggs a female has.

Mating is also a lengthy business for these tiny, busy flies. Mating can take two hours and involve several distinct rituals. During the two hour, multi-phase courtship and breeding the male may “dance” on the back of the female, involving raising and lowering of the wings, the body, and quick stepping. Once mounted, a female will walk or fly with her partner to the underside or periphery of the antler, to avoid harassment from other males. The male will tap and massage the female’s abdomen, a behaviour that may allow males to assess the reproductive condition (egg load) of females. Following mating, females expel and later ingest fluid droplets containing sperm, and likely nutrients, energy, and water transferred from their mates. These droplets serve as “nuptial gifts” provisioned by males and are a direct benefit to breeding females. Females deposit eggs into cracks and pores on the antler surface, often created from the chewing by small mammals, all the while being guarded by her mate.

After egg laying, females often leave the antler whereas males frequently resume mate searching in order to maximize the number of mating opportunities over their short lifetimes. Over half of male mating attempts are successful (57%), while many mating attempts are ended prematurely by at least one member of the pair (39%), and rarely, competing single males manage to displace the mating pair (4%).

Although, Russell’s research certainly supported the hypothesis that antler flies live their entire lives on antlers most adult flies spend their entire life on a single antler. To most of these flies a single antler is their entire world. The flies are also hosts other living organisms. The small flies carry even smaller parasites, including nematodes and mites on their outer body surface. A single antler can therefore be a unique ecosystem unto itself with a host of organisms that depend on the space and nutrients it provides.

The connection between antlers and the antler flies does not begin and end with us leaving antlers lying once we stumble upon them. It begins with us looking after animals that carry antlers. Only with healthy moose populations can these flies, and in fact entire micro-ecosystems, get a steady supply of living space. This should serve as a key example of the deep ecological interactions between the very different food webs that exist in the Canadian boreal forest.

Antler fly research webpage of Dr. Russell Bonduriansky www.bonduriansky.net/antlerflies.htm

Patrick Moldowan. Patrick is a student researcher and member of the Board of Directors at the Wildlife Research Station, Algonquin Provincial Park, where he conducts research on salamanders and turtles. Follow Patrick and his research at:www.patrickmoldowan.weebly.com.

Dr. Russell Bonduriansky. Russell completed his BSc and M.Sc. at the University of Guelph and his Ph.D. at the University of Toronto, spending his summers researching flies, ecology and evolution at the WRS. He then moved to Sydney, Australia, where he is now an Associate Professor at the University of New South Wales. He still studies flies.

Gananoque Lake Nature Reserve © Smera Sukumar

I don’t agree:

https://www.bestofthetetons.com/2015/09/02/antlers-and-wyomings-shiras-moose/