Ontario Nature Blog

Receive email alerts about breaking conservation

and environmental news.

© Lora Denis

Peat isn’t just something you put in your garden. In fact, it may be time to re-think using peat moss altogether. Recent research suggests that Ontario’s peatlands may be our largest carbon reservoir. However, mining them impacts their ability to sequester and store carbon.

With emissions on the rise, nature-based climate solutions like protecting peatlands provide us with a glimmer of hope for slowing climate change and increasing resiliency.

To get some insight into the wonderful world of peatlands, we interviewed Dr. Lorna Harris about her latest research. Dr. Lorna Harris is a peatlands expert in Canada whose work focuses on bringing awareness to Canada’s threatened peatlands. Her passion for peat is contagious, and we can’t guarantee that you won’t find yourself yearning to explore your local wetland after reading this! If this is the case, we urge you to grab a hand lens (for detailed mossy viewing) or some binoculars (you’ll want to check out the birds) and get out to your nearest wetland.

Q. How did you become interested in peatlands, and how long have you been working on this topic?

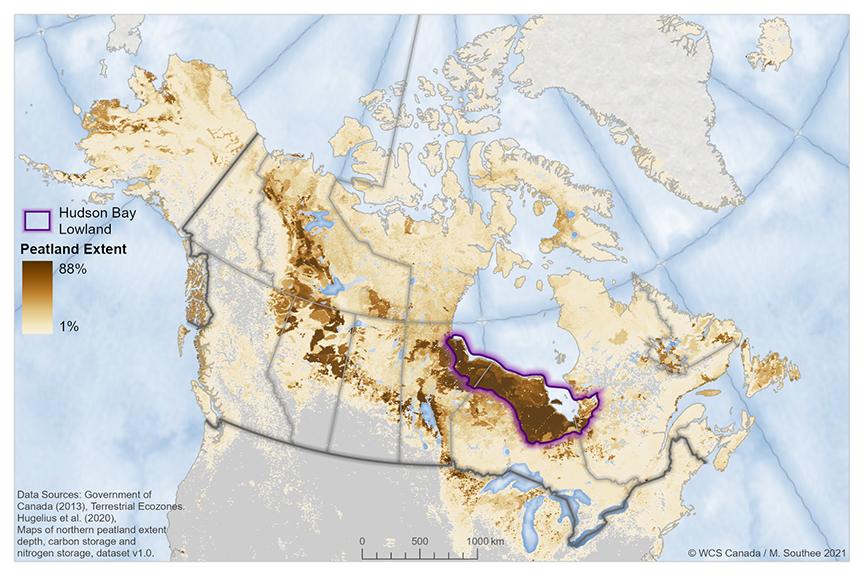

Dr. Harris: I started as a wetland ecologist in Scotland for around six years. Scotland has a huge amount of peatlands. The more environmental impact assessments I was doing there, the more I realized how little research there was on disturbance impacts to peatlands. I decided to complete my Ph.D. at McGill University studying peatlands in the Hudson Bay Lowlands. I have been researching peatlands across Canada ever since. I’m now working with the Wildlife Conservation Society to continue this research and to look at policy for peatland protection in Canada. Peatlands can be tough environments to work in, especially in Canada with the black flies, but I love being out on them!

Q. How are peatlands crucial to fighting climate change?

Dr. Harris: Peatlands are one of the best carbon capture and storage systems that we have. They’ve been developing for 10,000 years by taking carbon out of the atmosphere and decomposing slowly. In Canada, I’ve surveyed peatlands that are up to five meters deep, but they can be deeper. We assume that peatlands will continue storing carbon over time, but we risk losing that stored carbon if we disturb them. In terms of climate change, we want the peatlands to continue being a sink for a really long time. Along with being huge carbon stores, they’re also an important landscape for many different species and freshwater. The Hudson Bay Lowland has some of the last undammed rivers in North America, and the vast peatlands there are part of an important cultural landscape for Indigenous communities.

Q. What are the biggest threats to peatlands right now?

Dr. Harris: In Canada, we have a few different threats. Wildfires are a big threat, especially with the climate warming. If the peatlands dry out (or if we drain them or disturb them), you can increase the risk of fire ignition and increase the severity of fire. Canada also has a large amount of permafrost peatland, but climate warming is causing the permafrost to thaw. As the landscape thaws, a lot of the carbon in the peat that’s been frozen for thousands of years is released into the atmosphere. Other significant threats include development, infrastructure, seismic lines (kilometers of clearcut strips fragmenting the boreal forest for oil and gas exploration) and road development. The proposed Ring of Fire mining development in northern Ontario is a major threat to the carbon-rich peatlands in the Hudson Bay Lowland.

Q. What’s the next step for peatland conservation in Ontario?

Dr. Harris: Currently, there are no or very limited protections for peatlands unless they occur in a protected area. If development is proposed, I’m not aware of any specific legislation or policy that would prevent damage to peatlands. We need policy and legislation in place as there is little to none right now. We are just starting to gain some ground with peatlands [awareness], but there’s still so much more work to do. If more people get out into peatlands, they can see what they are and how interesting they are.

Q. What are the implications of not doing anything?

Dr. Harris: If we continue business as usual, we are making it a lot harder to reduce our overall greenhouse gas emissions and achieve our global climate targets. Canada’s peatlands are significant carbon stores, making their protection a global responsibility. We should be leading the way and learning from countries in Europe, which now have to spend millions to restore their damaged peatlands that are emitting carbon to the atmosphere. Restoring peatlands will take hundreds to thousands of years to get the carbon back that’s been released. Ultimately, we must ask ourselves – do we need to disturb or develop on pristine peatlands? We need to keep questioning these actions to hopefully lead us to a better outcome.

Want to help protect Ontario’s wetlands including peatlands and the species-at-risk that rely on them? Check out our wetlands campaign and sign our action alert to urge the provincial government to develop a clear action plan to recover species at risk and their habitats.

This project was funded by the Career-Launcher Internships program with the financial support of the Government of Canada through the federal Department of Environment and Climate Change, the Metcalf Foundation and an Anonymous Donor.

Gananoque Lake Nature Reserve © Smera Sukumar

Isn’t the “Ring of Fire” development something that Doug Ford and his government have been touting recently? If so, God help the peatlands and wetlands of Northern Ontario.