Ontario Nature Blog

Receive email alerts about breaking conservation

and environmental news.

© Lora Denis

Dog-strangling vine © Noah Cole

In the Cadotte Lab at the University of Toronto – Scarborough, we examine the causes and consequences of invasion success, biodiversity loss and changes in ecosystem services in Toronto’s Rouge Park, which is currently transitioning into Canada’s first National Urban Park.

In Canada, more than 80 percent of the country’s population lives in urban areas, making them critical centres for environmental engagement. Yet, urban areas are also human-shaped environments with highly altered landscapes and multiple land uses. Understanding the ecological systems in cities and the ecosystem services (explained in this factsheet) they provide is therefore becoming increasingly important in the pursuit of sustainable development.

Our work is largely aimed at understanding the effect of highly invasive dog-strangling vine (DSV) (Vincetoxicum rossicum) on multiple ecosystem services within Rouge Park, where its abundance has been steadily increasing in recent years. It is an exemplar invasive species because it is widely distributed and extremely abundant. High density populations can be found throughout southern Ontario, Quebec and in some northern states (DiTommaso et al. 2005).

In its native range of the Ukraine, DSV is considered a rare understory species, yet in North America it is extremely abundant and thrives in a wide range of environments including forests and open fields.

There are many hypothesized mechanisms that might explain DSV’s success in North America, but we are focusing on two primary ones. The first mechanism is related to DSV’s ability to match ecological requirements in different environments, often called phenotypic plasticity. This ability allows a species to reproduce successfully and thrive in different environments (Hulme 2007). Examples include achieving different heights and leaf shapes to optimize the conditions of different habitats.

The second mechanism we are investigating is called enemy release. It occurs when an introduced species’ abundance and spread is not regulated by an enemy such as an herbivore, and thus the introduced species outcompetes native species that are affected by herbivory (Colautti et al. 2004). Both of these mechanisms can lead to the introduced species becoming competitively dominant, which can thus lead to the competitive exclusion of native species.

To examine these two mechanisms we have been studying DSV from different habitats (e.g., closed forest canopies and open fields). We have found that DSV does indeed change according to local environmental conditions and are therefore able to reproduce successfully under very different environmental requirements. In order to get a better understanding of why this change occurs, we have started a greenhouse experiment where DSV roots collected from different habitats will be grown in alternate light environments.

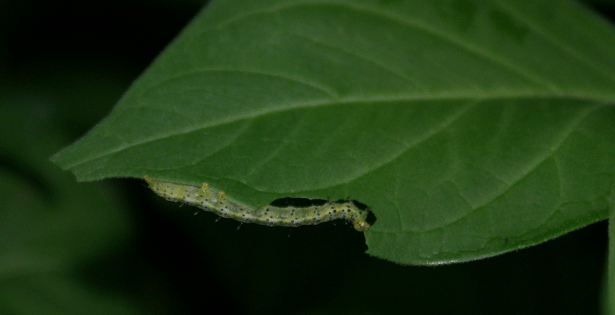

To examine the second mechanism, enemy release, we are currently looking at how DSV responds to defoliation or herbivory using the recently-approved biological control agent Hypena opulenta. H. opulenta is a moth that is found in DSV’s native range and has been shown to be a specialist herbivore, feeding only on DSV. Despite knowing that it is a specialist, little else is known about H. opulenta in terms of its ecology. Our research will demonstrate how DSV responds to herbivory, while also providing information on the moth’s response to different light conditions and potentially different food sources as we know that the plant characteristics are quite different in the two environments.

While it is critically important to research the causes of DSV’s success in North America, it is equally important to study and communicate the impact on ecosystems and related services. Furthering this understanding will help us galvanize public engagement and inform ecological restoration efforts.

Our initial findings suggest that DSV is having variable effects on ecosystem services. These findings are limited to meadows. Its impact in forests could differ, and there is definite concern that DSV hinders forest regeneration by choking out tree seedlings.

In meadow ecosystems DSV appears to be having no significant effect on productivity (biomass production) or soil carbon storage. Yet, we have observed significant declines in pollinator diversity and in nutrient availability at invaded sites. The most obvious effect of DSV invasion in both meadows and forests is a drastic reduction in native plant species richness.

The common theme in invasion ecology is that invasive species are outcompeting natives, reducing diversity and degrading ecosystem services. To study this, researchers will have to quantify ecosystem services in invaded and in non-invaded systems and consequently test how those services are being altered by species invasions and other anthropogenic forces.

Conserving the full extent of our native biodiversity is impossible. Contemporary rates of biodiversity loss have driven us into a state of conservation triage where we are forced to prioritize goals. Improving our understanding of both the causes and consequences of species invasions can bolster our ability to set those priorities.

Stuart Livingstone is a PhD candidate in Physical and Environmental Sciences at the University of Toronto – Scarborough. He is passionate about local ecology and the relationship between ecosystem processes and human well-being. His dissertation examines DSV ecology, impacts on ecological services and potential biocontrol.

Simone-Louise Yasui is a MSc candidate in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Toronto – Scarborough. Her research interests are invasion biology, plant diversity, ecosystem function and functional diversity.

Marc Cadotte is the TD Professor of Urban Forest Conservation and Biology for the Department of Biological Sciences at University of Toronto – Scarborough. He is also executive editor on the editorial board of Journal of Applied Ecology.

Proposed 413 Route, Old School Road with farm and escarpment view © Noah Cole

The app also contains a pretty extensive list of formulas that

calculus students have to memorize.

Didn’t the tests on the caterpillars and moths already take place in Ottawa’s Arboretum? Were they not released in small test areas last year after gaining approval? I also thought there were releases in the US of hypena?

Thanks for your comments and questions Natasha. Ontario researchers conducted eight years of lab testing on the Hypena moth before releasing it into a few DSV-infested sites in Ontario last year. It has not been released in the Rouge Park. Learn more in this ON Nature article: https://view.publitas.com/on-nature/spring_2015/page/12-13

Thanks… anything meatier than this article? Has hypena shown some degree of interest in eating any of the North American milkweed species? These would be new to it and while they are specialized eaters perhaps they (like the confused monarchs using dsv to lay eggs) can be fooled by the genetic similarities?

Hypena caterpillars (the adult moths do not eat) have shown no interest in consuming native milkweed species. If they had, researchers would not have progressed to field testing.

As for meatier articles, there are many online (see below for three). Contact U of T and Carleton U researchers for more info.

Related articles:

http://www.researchgate.net/publication/257468198_Biology_and_larval_feeding_impact_of_Hypena_opulenta_(Christoph)_(Lepidoptera_Noctuidae)_A_potential_biological_control_agent_for_Vincetoxicum_nigrum_and_V._rossicum

http://news.utoronto.ca/hungry-caterpillar-u-t-researchers-enlist-tiny-ally-fight-against-invasive-plant-species

http://newsroom.carleton.ca/2014/08/07/carleton-researcher-part-team-revealed-bio-control-agent-fight-invasive-plants/