James Bay peatlands © Ray Ford

What is Wetland Offsetting?

Wetland offsetting (often called “wetland compensation”) refers to the practice of undertaking intentional conservation measures to compensate for negative impacts on wetlands. The stated intent is typically to provide positive environmental impacts of an equivalent or greater magnitude and kind, with the offsets lasting at least as long as the harm to the original wetland.

Wetland offsetting often aims to achieve no net loss or ideally, a net gain in wetland area and values. However, evidence suggests that efforts to date have rarely even achieved no net loss. Wetland offsetting policy goals will almost always target wetland area and often also target some aspects of biodiversity and ecosystem function values. The social and cultural values of wetlands are rarely considered. However, evidence suggests that efforts to date have rarely achieved the goal of no net loss.

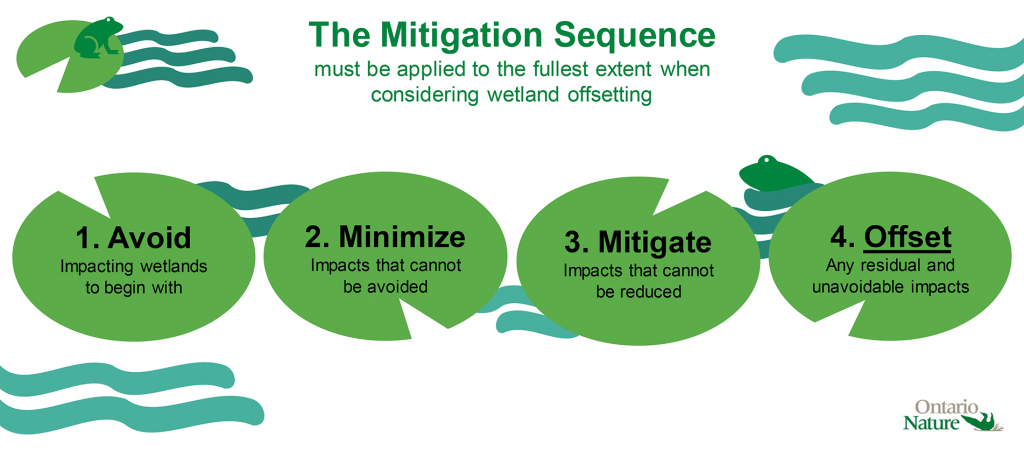

Wetland offsetting should only be pursued as a last resort, the final step in the mitigation sequence, which describes a series of stages to first avoid, then minimize, and then mitigate impacts from development before resorting to offsets to compensate for the residual damage.

Like-for-like Offsetting

Wetland offsetting should strive to ensure that the wetland being created or restored is reflective of the wetland being lost or degraded. This is called “like-for-like offsetting” and requires detailed study and documentation of the impacted wetland before it is removed so that a similar system can be recreated through the offsetting project. For the best chance of providing the same type and location of ecosystem benefits, the wetland offset should be located on the same property, or on a nearby site with similar characteristics. A monitoring and long-term management plan for the offset should also be established to ensure that the ecosystem continues to function and mature as intended.

Wetland offsetting may be undertaken directly by the developer responsible for the loss of the original wetland (called “proponent-led offsetting”) or by a third-party organization. Third-party offsetting can include individual offsets, in-lieu fee programs or mitigation banks.

Third-party Offsets

Individual Offsets The development proponent fully funds the third-party to produce an offset project to compensate for the damage caused by a specific project.

In-lieu Free (ILF) Programs The development proponent pays a fee to a third-party who collects payments from several smaller developments until sufficient funds have accumulated to fund a larger offset project (of ecologically relevant size) to compensate for the damage associated with all of their negative impacts. Fees typically cover the cost of acquiring the land, resources and labour for the offset project. Some programs also require a contingency fee in case some portion of the offset project fails.

Mitigation Banks A third-party creates a large continuous area of wetland offsets in advance of and not associated with development projects, and then sells offset “credits” to developers as they need them. The number of “credits” available from a “bank” depends on the size and quality of wetland area created or restored as determined by an independent evaluator.

Wetland Offsetting in Practice

In practice, wetland offsetting projects include activities that result in on-the-ground benefits for wetland ecosystem functions and biodiversity. This may include:

- the creation of an entirely new wetland where one did not previously exist, and/or

- the restoration or enhancement of an existing degraded wetland

Regardless of the approach, the financial burden of providing, monitoring and maintaining the wetland offset should fall squarely on the development proponent responsible for impacting the original wetland. It is important to ensure that the full cost of the offsetting project is calculated accurately so that sufficient funds can be secured from the proponent when the offsetting project plan is agreed upon.

Risks and Cautious Steps Forward

Wetland offsetting is a risky business that, to date, has seldom achieved full compensation for the damage done. While there are numerous potential risks associated with the practice, three prominent issues consistently arise: site selection challenges, time lags and failure to achieve no-net-loss goals.

Site Selection Challenges

- Each wetland type requires a specific set of conditions to form and maintain itself (including soil type, topography and hydrology, among others). Finding appropriate sites is especially difficult in heavily developed areas like southern Ontario.

- Wetland offsets should be located close to the impacted ecosystem to ensure the “replacement” wetland values (social and ecological) benefit the same areas and communities impacted by the loss of the original wetland.

- Again, finding appropriate sites is difficult in heavily developed areas. This often forces the offset provider to seek a more appropriate location further away from the impacted site or to settle for a site with nonideal conditions.

(Spence 2021; Yu et al. 2018)

Time Lags

- Wetland biodiversity often requires 10 to 1,000 years to recover after disturbance, even when supported by active restoration, highlighting the risk of extended “temporary” losses when wetlands are removed for development.

- This risk of “temporary” losses (or time lags) is especially pronounced for in-lieu fee offset projects as offsetting activities are delayed until sufficient funding is accumulated.

(Pezzati et al. 2018; Stephenson & Tutko 2018)

Failure to Achieve No-net-loss

- Research has consistently indicated distinct differences in the biodiversity and ecological function of wetland offsets compared to natural wetlands, with wetland offsets generally performing significantly more poorly.

- Wetland offsetting practice to-date has demonstrated a failure to achieve no net loss (i.e., provide the same degree of value), even if the offset is of equal size to the impacted ecosystem.

(Accatino et al. 2018; Price et al. 2019; Theis et al. 2019; Tillman et al. 2022)

Given the risks outlined above, wetland offsetting should be treated as a last resort. Where loss is unavoidable, meticulous implementation of strict offsetting protocols with high performance standards is of utmost importance.